Con Edison and Superstorm Sandy

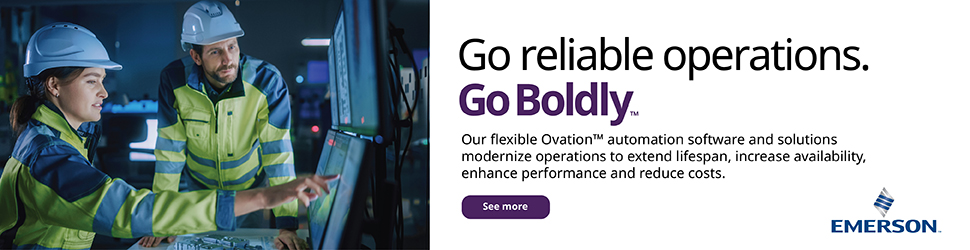

More frequent catastrophic events, weather-related or otherwise, are becoming a fact of life for generating facilities. When they occur, they focus the collective mind on minimizing the impacts from the next one. At Consolidated Edison Co of NY Inc’s East River Generating Station, recovering from “Superstorm Sandy” (Fig 1) offers some lessons learned and new practices for resiliency.

More frequent catastrophic events, weather-related or otherwise, are becoming a fact of life for generating facilities. When they occur, they focus the collective mind on minimizing the impacts from the next one. At Consolidated Edison Co of NY Inc’s East River Generating Station, recovering from “Superstorm Sandy” (Fig 1) offers some lessons learned and new practices for resiliency.

Sandy resulted in all manner of new concepts and “big think” projects for protecting Manhattan and the rest of the city from (1) incrementally rising seawater levels and (2) more frequent and more severe storms. Both are thought to be the projected consequences from long-term changes in global climate.

Manhattan of course is unique, for obvious and not so obvious reasons. In the latter category are the facts that it is a constrained load pocket with respect to electricity delivery and much of its infrastructure is relatively old. Let’s just say that adding, refurbishing, or replacing infrastructure in Manhattan is in a class by itself when it comes to complexity, permits, and regulations. Imagine trying to build a new powerplant on the island. Thus, existing, “close in” sites like East River become that much more valuable and critical.

The plant not only supplies 700 MW of electricity into one of the country’s most critical load pockets, but also 50%, or 5.8-million lb/hr to Manhattan’s extensive steam network, one of the largest in the world. Eight 345-kV transmission feeders tie into the plant, an indication of East River’s central role in the city’s electricity delivery.

Although the plant dates back to 1926, it was repowered and expanded in 2005 with two GE 7FA.03 gas turbines and two 600-psig heat-recovery steam generators (HRSGs), said to include the largest duct burners in the world. Five packaged boilers also were installed around 2001 and two older units—including one 1500-psig and one 1800-psig unit—still operate. The gas turbines were later upgraded to 7FA.04s which raised efficiency by 2.5% and output by 12 MW per unit.

The 7FAs at East River are baseload units because, like many cogeneration plants, electricity is a byproduct of steam production. Flexibility to produce both is paramount. The huge duct burners allow greater steam production, which is critical during the peak cold winter season. The boilers and HRSGs are dual-fuel; the plant has 15-million gallons of fuel oil stored at the site. Steam first enters a massive ring header before it heads out through distribution mains to the network. No condensate is recovered which makes water treatment that much more complex.

Sandy strikes

It was the rapidity of the storm “surge” as much as the delta height of the breach which combined to force the plant offline during Sandy. “There was six feet of water in the guard shack area at the entrance to the plant, and much critical equipment in the basement was immersed in three and a half feet of water at the apex of the surge,” said Michael Brown, plant manager. Basement level at the plant is 4.5 ft above river water level.

The plant is located in the lowest flood zone of the borough. Even though the plant staff began planning for the storm five days prior, nothing like Sandy had occurred before, so little could be anticipated. Plant personnel put sandbag barriers around critical equipment and relocated emergency and other vehicles to higher ground. Mains were isolated as a pre-emptive measure.

“It was three feet over a breach event recorded in 1821, and the plant was designed with one and a half feet of margin over the worst storm known at the time,” said Brown.

He continued: “The packaged boilers’ electrical distribution area was in real bad shape, three 13-kV transformers were damaged beyond repair, and we had to remove and refurbish 130 motors and pumps!” The arcing in one of those three transformers was responsible for lighting up the lower Manhattan night skyline, the image from the storm that made its way around the world.

Despite the calamity, the plant recovered house power by early Tuesday morning, less than 12 hours after the storm surge. The gas turbines were back in operation within two days. “We had to configure the operable equipment to get auxiliary power back,” added Brown, “we were fortunate to have 66 of the plant’s 200 staff who remained and worked tirelessly during the event.”

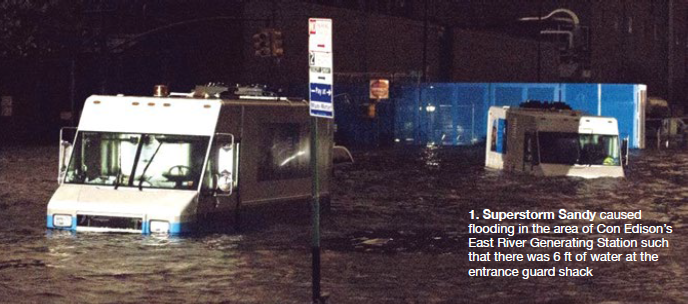

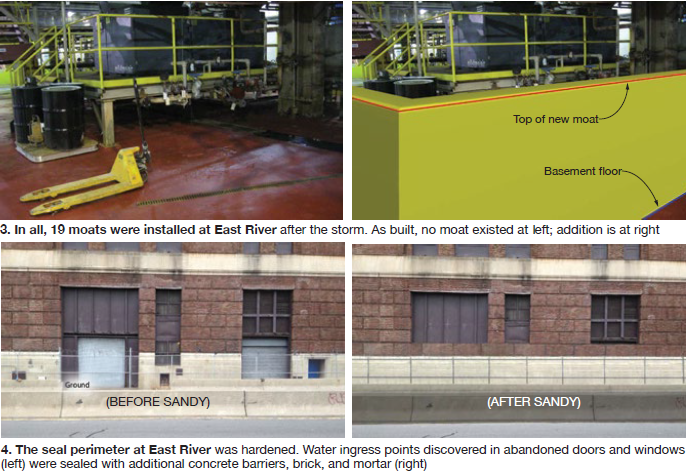

Some critical equipment already had flood protection but the utility has spent millions more at East River to make it more resilient the next time. Examples include:

- Pumps and motors at ground level, already protected by a moat, had walls raised by more than two ft (Fig 2).

- Drain manholes were added in strategic locations.

- Intake tunnels were closed and sealed off.

- Rigging beams were installed above critical pumps.

- Barrier door seals were added or hardened.

- Nineteen moats were added for equipment which had none before (Fig 3)—such as at the gas-turbine control cabinets—often with sump pumps, some as large as 1000 gal/min.

- Dozens of new floodgates were added at entrances for people and machinery, along with six trash pumps throughout the plant.

- The concrete perimeter around the plant was raised several feet in locations where water could enter, such as through old doors and windows (Fig 4).

- A backup diesel/generator was removed and reinstalled on an elevated platform consistent with the new design flood level of 18.2 ft.

Having its own machine shop in the Van Nest section of the Bronx helped Con Edison recover quickly. “We do all of our own repair, outage, and construction services work here—including that for 7FA maintenance,” Brown said. The plant keeps a full gas-turbine compressor shaft in storage at the company’s warehouse in Astoria, Queens.

One of the most difficult situations to deal with under these circumstances is water hammer. As most steam-plant engineers know, bad things happen when cold water hits high-pressure, high-temperature steam lines. Salty water also isn’t kind to most anything made of steel. The plant was fortunate to avoid any sustained damage from water hammer.

Con Edison’s budgetary documents available from the web show that the utility plans to spend $65-million on resiliency projects for East River between 2013 and 2017. Objective is to satisfy a new FEMA 100-year flood level plus 3 ft.

According to “Chapter 6: Utilities” from the document, “A Stronger, More Resilient New York,” issued by the mayor’s office (Bloomberg at the time), the city lost more than 90% of its steam production capability during the storm, and it took 12 days to restore it fully. Getting East River back online promptly obviously contributed mightily to restoring essential energy services to the city.

What’s more, 88% of its steam generating capacity, 53% of in-city electric generation, 37% of transmission substation capacity, and 12% of large distribution-system capacity lies in the 100-year flood plain. All of those figures are expected to grow in the coming decades.

High-profile customers

East River is justifiably proud of its role in serving the city’s steam needs (Fig 5). After all, you can’t get higher profile customers than The United Nations, World Trade Center, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rockefeller Center buildings, marquee New York hospitals, and major high-rise residential and office complexes.

One interesting attribute of Con Edison’s team quality is that it is “FDA-compliant,” which means it can be used directly for such functions as sterilization and humidification, the latter essential, for example, in preserving art works in museums. GRiD