Toledo emerges as an industry leader with state-of-the-art cogen plant to power critical facilities

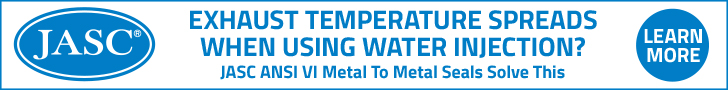

The Bay View Combined Cycle Cogeneration Facility is a project surely to be appreciated by power-generation professionals (Fig 1). It has the ability to burn both conventional and “green” fuels separately or simultaneously in both its gas turbine and heat-recovery steam generator (HRSG). Also, and perhaps more importantly, the facility is designed for maximum operational flexibility to provide the City of Toledo’s Div of Water Reclamation (DWR) the level of reliability it needs to assure continuity of operations at the critical Bay View Wastewater Treatment Plant (Sidebar 1).

Most people do not think of sewage treatment plants as “critical” facilities, nor do they associate them with the need for a highly reliable supply of electric power. But environmental rules impacting wastewater-treatment operations have become more demanding in recent years, as they have for powerplants. When you’re handling 2.5 million gal/hr of liquid waste on average, even a brief outage can seriously upset flows and water chemistry—and possibly lead to fines.

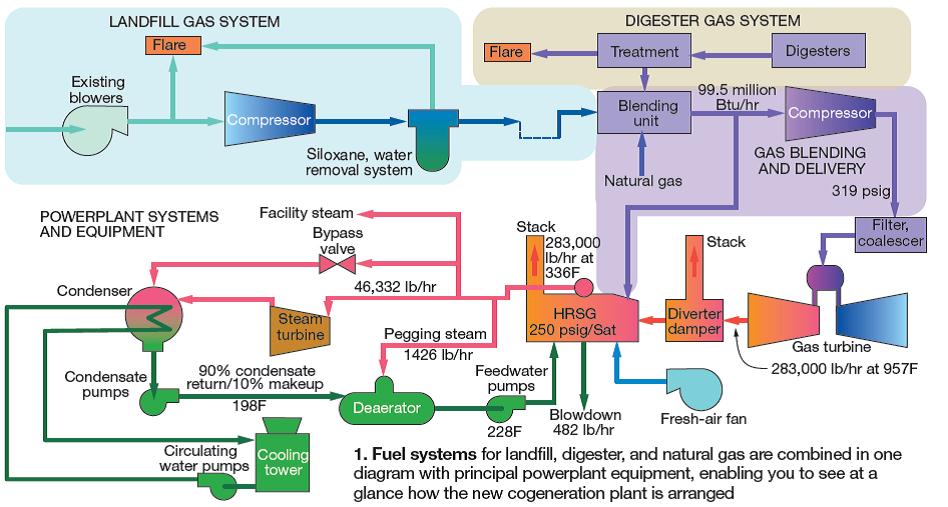

Continual improvement of water treatment processes is engrained in Bay View’s culture. A quick read of the sidebar on the facility’s history is proof of that. However, it wasn’t until after the millennium that serious attention was focused on the single 69-kV line supplying Bay View’s electricity through a 10-MW 69/12/4.16-kV substation. There was no alternative source of power. Reliability engineers viewed this as a serious weakness; so did the EPA.

In 2004, a backup generating facility was incorporated into the mechanical equipment building (No. 17 in the aerial photo accompanying Sidebar 2, which explains how Bay View works). Three 33,350-cfm motor-driven centrifugal blowers were installed as well, to replace the engine-driven blowers that had been providing air to the aeration tanks (Fig 2). Six Caterpillar engines with a combined capability of up to 12 MW were added to the existing 1.6-MW diesel/generator shown in Fig 2C. One of the six is a black-start unit, three are powered by natural gas, two can burn green gas or natural gas.

Motivation for installing a 10-MW, Taurus™ 60-powered 1 x 1 combined cycle capable of burning gas collected from the city’s Hoffman Road Landfil,l as well as gas produced by the wastewater-treatment plant’s digesters, included the following: (1) reduced emissions from city operations (improved local air quality), (2) reliability benefits of onsite generation, and (3) lower cost of electricity. The cogen plant began commercial operation in fall 2010.

The city’s project manager for both the engine-based backup generating facility and the combined cycle was Michael Schreidah, PE, a 22-yr veteran with the Dept of Public Utilities (DPU) within the DWR. Engineer on the cogen project was Middough Inc, Cleveland; constructor was Barton Malow Co, Southfield, Mich. Middough’s primary interface with the city on the combined cycle was Martin F Ellman, PE, senior manager for energy technology. He talked to the editors about the project’s special requirements/challenges. Among them:

- Design the plant for base-load operation on landfill and digester gases; initial thinking was that natural gas would be an emergency fuel. However, at the rate of green gas production today, the cogen plant is limited to about 3.5 MW on landfill and digester gases. Natural gas must be added to the fuel mix to produce more power.

- Provide the flexibility to run the combined cycle at about half load most of the time, but have the ability to produce up to 10 MW during periods of abnormally high wastewater flows. Ellman said 4.5 MW or less is required to operate the treatment facility most days.

- Arrange the combined cycle to operate in parallel with the grid and the engine generators.

Project organization. The Bay View cogen project had three major elements of interest to powerplant engineers:

1. Gas treatment and blending systems and equipment (Solar Turbines).

2. Combined cycle and balance-of-plant systems (Solar Turbines).

3. Landfill gas pipeline, 5-kV feeder to supply power to gas treatment equipment at the landfill, natural-gas pipeline extension, and fiberoptic link between the cogen plant and landfill (InfraSource, a Quanta Services company, Glen Ellyn, Ill).

Landfill gas system.

The Hoffman Road Landfill, located about two miles from the cogen plant (No. 3 in the aerial photo below), began operating in 1974, well before the power project was conceived. It is expected to remain in service for 15 to 20 more years and produce enough gas to support power-generation activities for another 25 to 30 years.

Schreidah said that during the design phase of the combined cycle, the city expected the landfill to provide 1500 scfm of gas with a heating value of between 500 and 550 Btu/scf. But the downturn in the economy has had a negative impact on gas production, now at about 1150 scfm. Methane typically comprises 45%-55% of landfill gas, with most of the remainder CO2 (45%-50%). Hydrogen the next most common constituent at 1%-5%.

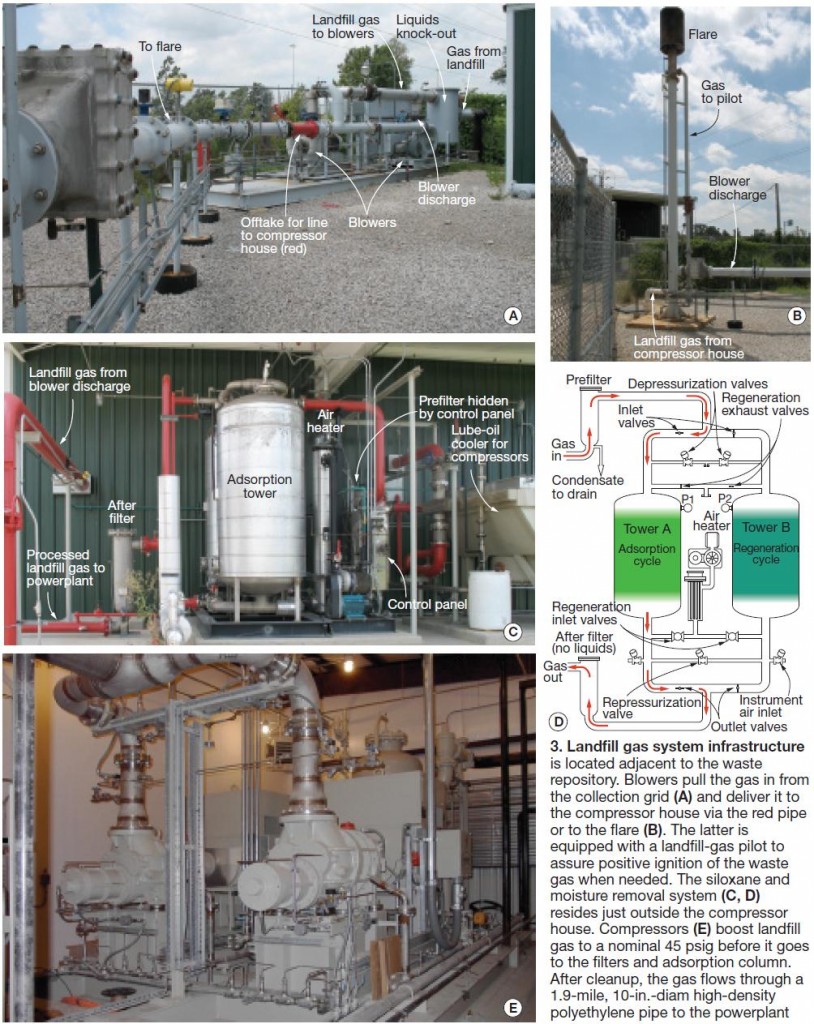

Before the combined cycle was built, gas was flared (Fig 3). Toledo’s Dept of Public Service, which operates and maintains the landfill, had been trying to sell the gas for years but was unsuccessful until the idea of building a cogen plant gained support. Although DPU, the combined-cycle “owner,” is a sister agency to DPS, a fuel-supply contract is in place and DPU “pays” DPS for the fuel.

The basic flare system in Fig 3A existed before the cogen plant, but it was upgraded as part of that project. The red spool piece in the middle of the photo, a tee, was added to direct landfill gas, previously flared, to the adjacent compressor building and treatment system where the green gas is cleaned-up before being piped to Bay View. Project engineer for this work was Mike Kemp of HCS Group Inc, Houston, a subcontractor to Solar Turbines.

In addition, a small line was run from the discharge side of the landfill-gas compressors to the flare. The green gas it delivers supports the flare’s pilot flame (Fig 3B). Note that the flare is a critical component because it destroys gas that otherwise might be released to atmosphere in the event of a system upset. Release of landfill gas to the natural environment is not permitted by law. Operation of the landfill-gas collection system and flare are monitored from the cogen plant.

There are two fundamental steps in landfill-gas processing at Hoffman Road: compression and siloxane removal (Sidebar 3). Keep in mind that the fuel contains a significant amount of moisture which should be removed before it is sent to the gas turbine. Alternatives: Install a refrigerated dryer in the gas line ahead of the compressor or opt for a dewpoint suppression system.

The siloxane removal system in Figs 3C and D, supplied by Parker Hannifin Corp’s Purification, Dehydration & Filtration Div, Charlotte, NC, has these three stages of treatment:

1. A high-efficiency, low-pressure-drop coalescing prefilter for removing solids, liquids, and aerosols down to 0.01 micron to protect the media beds.

2. A regenerative adsorption system to remove siloxanes.

3. A 1-micron after filter to protect downstream equipment from any dust particles created as the media wears.

Here’s how the adsorption system works: Landfill gas flows down through a bed of adsorptive media which has an affinity for siloxane molecules and other contaminants. One bed in the twin-tower system is in service while the other is being regenerated or is on standby following regeneration. A service run typically lasts 24 hours, regeneration takes 12.

During regeneration, heated ambient air is passed upward through the media (direction is opposite to that of gas flow in the active adsorber). Heat breaks the bond between the media and the siloxanes; the latter are transported by the air stream, along with residual hydrocarbons, to the flare. When incinerated in the flare, the siloxanes morph into small crystals of silicon dioxide (sand) which dissipate into the ambient air.

The Parker system is relatively new. Brad Huxter, market development manager for the company’s Green Energy Solutions product line, said Parker purchased the UK’s dominick hunter ltd (official company name was in all lower-case letters) in 2006 and the siloxane removal system was among the company’s assets for filtration, purification, and separation of compressed air and gases.

After about 10 years of R&D work, the first commercial units entered service in fall 2007. Since then, more than 30 systems have been sold and are protecting fuel cells, reciprocating engines, and gas turbines from siloxane fouling. Huxter said specifications for new systems indicate the industry has settled on a performance spec that calls for less than from 5 to 10 mg/m3 of siloxane in the product gas stream.

As an example of the system’s value to engine operators, Huxter added that one owner reports its maintenance intervals have been extended three-fold compared to operation without siloxane removal. To date, only three siloxane removal systems have been purchased for clean-up of digester gas; the remainder are operating on landfill gas.

Digester gas and blending

Anaerobic digesters identified by the number 8 in the aerial photo convert primary sludge, and some secondary sludge, to a 650 Btu/scf gas (Fig 4). However, the flagging economy has adversely impacted production of digester gas as it has landfill gas. Expectations were that 350 scfm would be provided by the digesters, but they are delivering only 250 scfm.

Digester gas also is passed through a siloxane removal system of the type used at the landfill. Only difference is size: The landfill system is rated 2000 scfm, the system for the digesters has one-fifth that capacity.

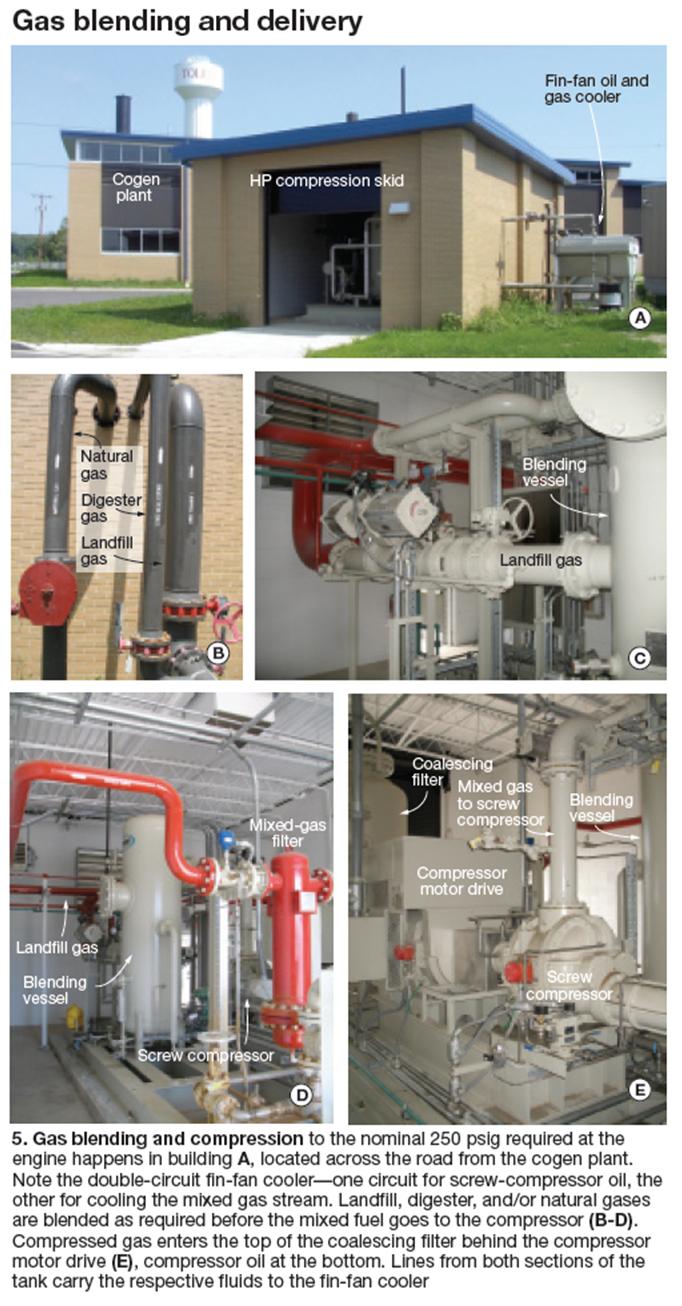

Gas exiting the landfill siloxane removal system at about 45 psig travels 1.9 miles to the fuel preparation building adjacent to the cogen plant via a 10-in.-diam high-density polyethylene pipeline. By contrast, the journey for the 30-psig digester gas is only several hundred feet. Natural gas is supplied to the building as well (Fig 5B), by Columbia Gas of Ohio.

Gases are blended as required (Figs 5C and D), compressed (Fig 5E), and forwarded to the gas turbine. The same mixed gas can be used in the HRSG duct burner if the gas turbine is out of service. However, the HRSG would not be supplementary fired with green gas at the same time the gas turbine is because there’s not enough landfill and digester gas to support that mode of operation.

Interesting to note is that there are redundant LP gas compressors at the landfill, but only one HP compressor. Reason: The HP compressor is backed-up by natural gas, which is supplied at a pressure compatible with turbine requirements. There is only one LP compressor for the digester-gas circuit.

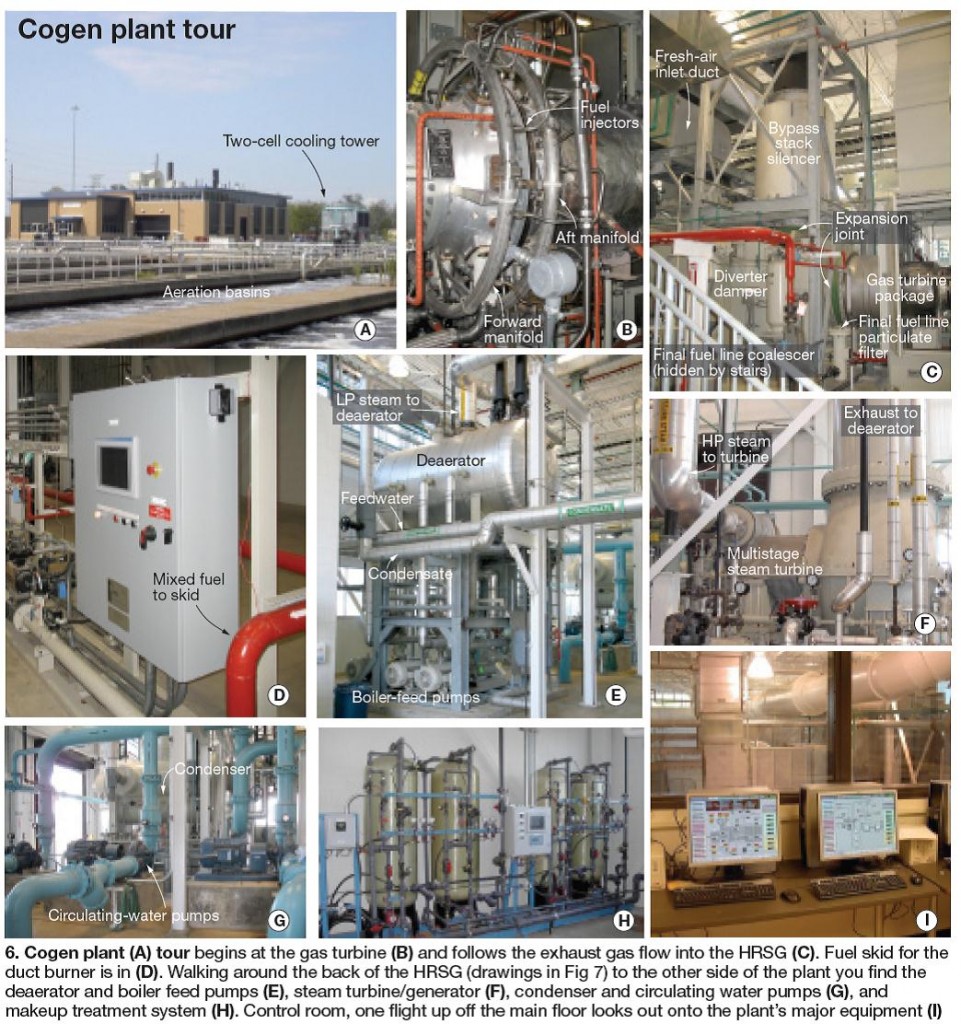

Schreidah said the gas blending and delivery system (purple area in Fig 1) works well. Quarterly, he added, gas is analyzed at the landfill, digesters, and at the blending station for siloxane, moisture, heating value, etc. Mixed gas entering the cogen plant (Fig 6A) passes through a small coalescer and final particulate filter just ahead of the gas turbine (Figs 6B and C).

The Solar Taurus™ 60 is rated at 5 MW when operating on green gas (capability is based on 1500 scfm of landfill gas, 350 scfm of digester gas). The project manager explained that the plant was commissioned on natural gas first and then on the green gas mixture to verify contractual requirements.

Project goal, Schreidah continued, is to use the green gases to sustain the electrical needs of the Bay View plant in dry weather. This is achieved most days. Depending on gas availability and other factors, the Taurus might burn (1) any one of the three gases by itself, (2) a mixture of any two gases, or (3) a mixture of all three.

Designing gas turbine combustion and control systems to accommodate a wide range of fuels requires considerable know-how. At Bay View the challenge was to assure safe, efficient, and reliable operation on natural gas with a heating value of about 1000 Btu/ft3 as well as on landfill gas with a heating value half that amount.

Recall that gaseous fuels normally are classified by their Wobbe Index, a parameter that accounts for variations in fuel density and heating value. It relates relative heat input to a combustion system of fixed geometry at a constant fuel supply pressure. If two fuels have the same Wobbe Index, direct substitution is possible and no change to the fuel system is required. A rule of thumb is that gases having a Wobbe Index within 10% of what the combustion system is arranged to handle can be substituted without making adjustment to the fuel control system or injector orifices.

Obviously, the range of Wobbe Indexes for the fuel combinations possible at Bay View are well beyond the 10% variation that can be accommodated by a standard combustion system. What Solar Turbines provided for the Toledo project was its dual-gas wide-Wobbe fuel assembly equipped with dual-gas low-Btu wide-Wobbe injectors shown in Fig 6B. Details on how the combustion system works were not available.

The heat-recovery steam generator, designed and built by Rentech Boiler Systems Inc, Abilene, Tex, is, perhaps, the first HRSG designed to burn 100% green gas as a supplemental fuel (Figs 6C and D, and Fig 7). Such innovation is in sharp contrast to the balance-of-plant (BOP) equipment, which basically is “standard issue” (Figs 6E-I).

On a typical dry day, gas-turbine output on 100% green gas would be 5.1 MW and the HRSG would generate around 19,000 lb/hr (about 22,000 lb/hr were the GT burning natural gas) with the duct burner turned off. The steam turbine (ST, Dresser-Rand Co) would produce a nominal 1.5 MW—its minimum output.

The supplementary firing system, provided by Coen Company Inc, Foster city, California normally burns natural gas because, as noted earlier, the GT consumes all the landfill gas and digester gas produced at this time. With the 65-million-BTU/hr duct burner at full fire on natural gas and the gas turbine operating at rated output, the boiler generates 77,000 lb/hr of 650-psig/700 steam, good for 5.1 MW from the multi-stage steamer.

Gas produced in up to six anaerobic digesters flows from the spherical storage tanks highlighting the photo to the gas blending and compression station a few feet from the powerplant. Flare in the foreground is available for use when upset conditions dictate.

The bypass stack and damper between the GT and HRSG are critical because they provide the flexibility to operate the gas turbine if downstream equipment—boiler or steamer, for example—is not available, and allow the Rankine Cycle to operate if the GT is out of service.

The fresh-air fan (FAF) enables duct-burner operation if the gas turbine is unavailable. It is designed to match the mass flow through the HRSG that the GT would normally provide. In this service mode, the steamer can produce 3 MW when firing green gas or natural gas. Obvious choice would be landfill and/or digester gas if available.

Use of special augmentation blowers (shown above the fresh-air fan in Fig 7 plan view) is required in addition to the FAF when burning green gas, to assure sufficient oxygen for complete combustion under all operating conditions. Note that no means is provided for controlling air flow from the FAF; steam pressure is controlled by modulating the fuel valve when the gas turbine is not in operation.

Ellman said upgrade of the HRSG to produce full output from the steam turbine with the GT shut down was considered, but that would have required having the boiler oversized, meaning it would operate at significantly lower efficiency most of the time. The economic penalty could not be justified.

Rentech’s project manager, Cory Goings, PE, told the editors that the superheater visible in the middle of the waterwall section of the HRSG was arranged in two passes with tubes oriented horizontally. Saturated steam enters the downstream section of the superheater (easy to see in the plan view), exits to a desuperheater, then re-enters the furnace area for a second pass. A two-pass design was necessary to control steam temperature under all firing conditions.

The economizer and condensate preheater are arranged in a separate section of the HRSG downstream of the waterwall boiler. The preheater has finned tubes of a duplex stainless material to minimize corrosion. The 0.375-in.-high fins also are stainless and arranged two fins per inch. Applied Heat Recovery LLC, Fair Oaks Ranch, Tex, made the economizer/preheater section for Rentech. Both companies are members of the American Boiler Manufacturers Assn, Vienna, Va.

Operational notes

Operation and maintenance of the Bay View cogen plant is under long-term contract to Solar. The contract provides for a bonus when plant availability is above the number specified, a penalty when below. Rick Bullard, Solar’s Bay View contract manager (plant manger) has more than two decades of industrial power experience, including combustion of landfill gas. He has a staff of six for 24/7 operation.

It made dollars and sense to have the complex plant run by an experienced team with direct access to engineers with first-hand knowledge of green gas treatment and combustion. Plus, a data feed to the Monitoring and Diagnostic Center at Solar headquarters assures that any operational anomalies get a second look.

Schreidah said the plant has successfully tested its ability to export power to Toledo Edison; plus, the utility has authorized two-way operation based on the positive results of its circuit-switcher test. At this time, the plant will only take power from the utility if need be.

This article would not be complete without mention of the cogen plant’s air permit, which specifies emissions limits on a tons-per-year basis for carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), NOx, and SO2 for both the gas turbine and HRSG.

Emissions limits are identified for each combustion source because the GT and boiler can be operated independently of each other.

The limits adopted by the Ohio EPA are based on the plant’s use of “best available control techniques and operating practices.” The state EPA noted that the design of the “emissions units” and the technology associated with the current operating practices satisfy its best-available-technology requirements.

Schreidah wrapped up the interview by saying that the air permit would not impose any operational restrictions on the combined-cycle cogen plant. Based on the quantities of landfill and digester gases available, he continued, the Bay View project always will be in compliance with the air permit.

Bay View: A Brief History

Bay View, the largest wastewater treatment facility in Northwest Ohio, is located in Toledo near the mouth of the Maumee River. It has a service territory of about 100 mi and receives water from industrial, domestic, and commercial sources. Federal, state, and local regulations governing the operation of, and discharge requirements for, wastewater treatment plants have evolved over the years just as they have for powerplants. Toledo’s first wastewater collection facilities were constructed in Bay View Park in 1922 on the site of the world’s first heavyweight championship fight between Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey (the winner) held three years earlier.

Primary treatment ordered by the Ohio Dept of Health began in mid 1932 and by the late 1930s primary settling tanks, a sludge digestion system, and chlorination facilities had been added. Secondary treatment using the activated sludge process commenced in 1959, with large diesel engines driving the air blowers required.

In the mid 1960s a new sludge dewatering facility and filter building were constructed and in 1969 the primary and secondary systems were renovated and expanded. That work was followed by enhancements to, and expansion of, the wastewater collection system in the 1970s. In the 1980s, tens of millions were spent to renovate, upgrade, and expand all processes and equipment at Bay View to meet more stringent regulatory requirements.

The 1990s brought still more improvements—including a new sludge stabilization facility, upgrades to electrical systems and controls, new final clarifier, enhancements to oil and grease skimmers and grit collection, etc. Between 2005 and 2007, $90 million was invested in a “wet weather” treatment process which included the largest ballasted flocculation system in the nation and a 25-million-gal equalization basin.

Obvious from the foregoing is that Bay View embraces a culture of continuous process improvement to assure world-class reliability and efficiency of the 24/7 facility. The same culture is embraced by staff responsible for site’s energy systems, which enable the massive plant’s operation.

How the Bay View Wastewater Treatment Plant works

Bay View treats water from both sanitary sewers and storm drains. Water received from the center of Toledo is a mixture of the two; other storm drains in Bay View’s service territory are released to receiving streams or pumped to the plant separate from sanitary-sewer wastewater.

Average dry-day flow (no precipitation) to the plant is 60-million gal; interestingly, it was about 25% higher before the recession. Typical wet-day flows can be three or four times greater than dry-day flows. Highest one-day peak rate to date was 405-million gal.

Capacity of the core plant is 168 million gal/day through primary treatment, up to 212 million gal/day can flow through secondary (biological) treatment. The wet-weather facility (WWF) added as part of a 2005 consent decree with the US EPA can process up to an additional 195 million gal/day. The WWF essentially accomplishes everything that the core plant does (primary and secondary treatment)—except for promoting the growth of anaerobic microorganisms to break down organic matter. That’s not necessary for the very dilute wastewater stream (mostly storm drains) it handles. The wet-weather facility operates only about 10 times annually.

Bay View is operated by Toledo’s Div of Reclamation, which also is responsible for all the wastewater storage and pumping facilities in the city. An onsite staff of 110 assures reliable and efficient 24/7 operation of the wastewater treatment plant within permit limits.

Treatment steps

Follow the flow of wastewater through the treatment plant using the aerial photo provided. Raw sewage is received by main pump station (4) after passing through fine bar screens to remove debris. First process step is grit removal (5) in aerated tanks. On a typical day, from 5 to 10 tons of sand, gravel, and other heavy solids are extracted from the waste stream and sent to the city’s landfill for disposal.

Skimming tanks to remove oil and grease are next (6). “Floatables” are collected here and transferred to scum separation tanks. Sludge settles to the bottom of the tanks and is pumped to the sludge thickeners.

First chemical treatment step is primary clarification (7). Polymer is added to the wastewater stream to promote solids settling. Floatables are skimmed and sent to landfill; solids are extracted from the bottom of the clarifiers and pumped to the digester tanks (8), which produce the methane gas burned by the new cogen facility.

Storage tank (10) receives sludge from the digesters before transfer to the dewatering facility (20). There solids content is increased by belt filter presses before transport to the sludge treatment facility (11).

Aeration tanks (12) mix air with wastewater to promote the growth of aerobic microorganisms which help break down organic matter. Secondary clarifiers (14) encourage floc, which contains microorganisms and organic material, to settle, leaving clarified water on the surface.

This process creates return activated sludge, which is sent back to the aeration tanks, and waste-activated sludge, which is processed in a dissolved-air floatation step. Latter adds polymer to the sludge and mixes it with pressurized water. Floatables are skimmed and pumped to the digesters, remaining water to the aeration tanks.

Chlorine contact tanks (13) disinfect clarified water with the powerful oxidizer between April 1 and October 31. A dechlorination step (21) precedes discharge to the Maumee River (2) via the final-effluent pump station (15).

What’s all the fuss about siloxanes?

Mark Hughes of Solar Turbines Inc provided a backgrounder on siloxanes of value to all considering green gas for power generation. Siloxanes, he said, are a group of unreactive chemicals used primarily as a replacement for oils in cosmetics—such as hand creams, stick deodorants, etc. They have an oily feel, but evaporate at body temperature.

There are hundreds of different species in this family of chemicals. Some are water soluble, Hughes continued, but these are less prevalent than the non-water soluble species. That’s a positive because they are the most difficult to capture.

Regarding experience, Hughes said his research has not revealed any documented evidence of gas-turbine component degradation caused by siloxanes—at any firing temperature. And Solar’s experience confirms that. The company’s first turbine to operate on landfill gas—a Centaur®40 at the Puente Hills Landfill in Whittier, Calif—has run more than 50,000 hours between overhauls with no ill effects.

Hughes believes there about 110 gas turbines operating on landfill or digester gas—fewer than 10% of them with the benefit of siloxane removal. Siloxane residual is invariably found on hot-gas-path parts (combustion liners and turbine airfoils) and typically results in a minor impact on performance, but no adverse effect on emissions.

Removal of siloxane deposits does not complicate overhaul processes or noticeably add to their cost.

However, Hughes suggested removing siloxanes from any fuel burned in reciprocating engines. It fouls plugs, coats cylinder heads and valves, and impedes the combustion process; CO emissions increase dramatically over time. Because of the potential for siloxanes to foul Solar’s Mercury™ 50 GT recuperator, siloxane removal is strongly recommended for that turbine.